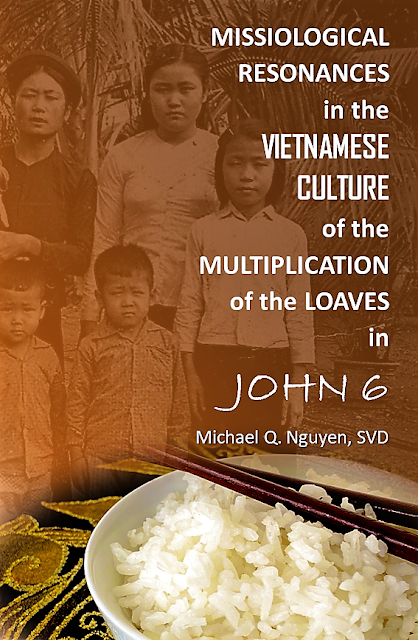

A Journey from Bread to Rice

PREFACE: A JOURNEY FROM BREAD TO RICE

This book is the fruit of my study at the Divine Word Institute of Mission Studies (DWIMS) in Tagaytay City, the Philippines.

The first question my advisor asked me at our first meeting for this project was: “Out of the seven signs in the Gospel of John, why do you select the account of the Multiplication of the Bread?” Likewise, the readers of this book might also have a similar question while glancing at the title of this book, Missiological Resonances in the Vietnamese Culture of the Multiplication of the Loaves in John 6.

First, this question relates to childhood when my family in Vietnam faced difficulties in providing steamed rice for the family meal table. As a teen, I vividly recall my mother’s face turning pale whenever my sister informed her of the reality, “Mom! There is no more rice in the jar.” As the “interior mistress/nội tướng” of a household consisting of nine members, including herself, my mother would have solid reasons to be so frantic that her face would change color. For the Vietnamese, if there is no more steamed rice on the meal table, starvation is on its way.

Secondly, this childhood experience reminds me of a moment, when I learnt in a Bible course that Jesus as reported in the Gospel did not eat steamed rice but bread as the staple food in his daily meals. At that particular moment, just like a person who was awakened, I tapped on my forehead, saying to myself, “No wonder all the meals that he shared with his friends and people were served with bread.” Consequently, I figured out the reason why the Jewish Jesus in John 6 declared to the Jewish people in Capernaum, “I am the bread of life” (John 6:35). My childhood experience of rice shortage and the knowledge that Jesus enjoyed a loaf of bread in his daily meals triggered the thought of undertaking a journey, I call, “from bread to rice.”

Thirdly, I was even more motivated as I learnt that “[there] is no such thing as ‘theology;’ there is only contextual theology”[1] which attempts to understand the Christian faith in a particular context. While the classical theology covers only “two loci theologici (theological sources) of scripture and tradition,”[2] contextual theology is comprised three theological sources; i.e., the Scriptures, the Christian tradition and the present human experience.[3] The last item in this list is the context of the Christian faith. Through the contextualization of theology, people of a particular culture with their present human experience will come to grasp God’s revelation through the person of Jesus as depicted in the Gospel within their own sociocultural context. As a result, contextual theology is not an option, but rather an imperative.[4]

Fourthly, in the Divine Word Institute of Mission Studies, I learnt that since Vatican II, the Council Fathers explicitly instruct the faithful to do mission by inculturation, i.e., mission as dialogue with culture. In Gaudium et Spes (GS), Vatican II declares, “The Church learned early in its history to express the Christian message in the concepts and languages of different peoples and tried to clarify it in the light of the wisdom of their philosophers: it was an attempt to adapt the Gospel to the understanding of all and the requirements of the learned, insofar as this could be done” (GS 44). What is more, the Council Fathers remind the missionaries in the contemporary world that inculturation should not be treated as an option, but “must be the law of all evangelization” (GS 44). Likewise, the Federation of Asian Bishops’ Conferences (FABC) urges the leaders of the Asian churches that in order to preach the Gospel effectively to the Asians, “we must make the message and life of Christ truly incarnate in the minds and lives of our peoples.”[5] Similarly, the Asian Bishops of the Special Assembly for Asia of the Synod of Bishops in 1998 suggest a way of doing mission as dialogue with culture in a way that speaks directly to Asians.[6] They therefore come up with the images of Jesus “which would be intelligible to Asian minds and cultures, at the same time, faithful to Sacred Scripture and Tradition.”[7] Two of these are Jesus as the Spiritual Guide and Jesus as the Enlightened One, which can be seen as Jesus as the Guru and Jesus as the Buddha respectively.

With a background that consists of my childhood; the common knowledge about the Jewish Jesus vis-à-vis his daily diet; the imperative of doing contextual theology; and the teachings of the Council Fathers, the FABC, and the Bishops of the Asian Synod concerning inculturation; I started “a journey from bread to rice” through a study of the account of the Multiplication of the Loaves in John 6 in the Vietnamese cultural context.

The aim of this book is to propose a new way of doing mission as dialogue with the Vietnamese culture, so the Gospel can be read through the Vietnamese eyes and within the context of the Vietnamese culture. I therefore examine missiological resonances in the Vietnamese culture of the episode of the Multiplication of the Loaves in John 6. From the points of convergence between the Vietnamese meal and the Jewish meal as implied in John 6, a missiological amplification emerges.

The Vietnamese culture is the agrarian culture of wet-rice. Thus, rice is the food of life for the Vietnamese. The Vietnamese people enjoy their daily meals served with steamed rice for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. In their own mindset, a meal is definitely not a meal without being served with at least a bowl of steamed rice. A loaf of bread, to the Vietnamese mind, cannot fill an empty stomach. Simply put, when the Vietnamese people are hungry, they will search for a bowl of steamed rice. Rice is not only significant to the living but also the dead. In a funeral, one can see on the lid of the coffin a bowl of steamed rice placed in front of the picture of the deceased. The principal foods of the Vietnamese meal consist of rice, vegetable and fish. Nevertheless, a frugal meal can just consist of steamed rice and a small bowl of fish sauce. Thus, rice is so significant that the absence of steamed rice at mealtime can be interpreted as a sign of severe famine.

Bread is the food of life for the Jews; it is the soul of the Jewish meal. Bread is baked and served in every single meal in Jewish society. Other dishes can be omitted on the meal table, but bread must always be served. Bread is so significant that when the situation calls for it, a Jewish meal can be served just with a loaf of bread. That is why the reader of the Bible notices that bread appears in the meal in the mountain in John 6. Above all, bread is what the Jews consume in order to survive. The absence of a loaf of bread on the table at the time of a meal can be seen as a sign of famine. Jesus employs the image of bread in his theological discourse in John 6 because bread is an essential food for life for the Jews. In saying, “I am the bread of life,” Jesus simply stresses the significance of believing in him as the bread that nourishes unto eternal life. Thus, without having Jesus as the Bread of Life, no one can survive.

In the world of the Vietnamese people rooted in the agrarian culture of wet-rice and speak the Vietnamese language, where the daily meal is served with the steamed rice/cơm, I propose:

First, the Multiplication of the Loaves in John 6 or the Eucharistic Meal of [Bread] can also be missiologically seen as the “Eucharistic Meal of Steamed Rice/Bữa Cơm Thánh Thể;”

Secondly, Jesus in John 6 can be seen as “Jesus, the Steamed Rice of Life,” or “Jesus, the Cơm of Life,” or “Chúa Giêsu, Cơm Hằng Sống” in Vietnamese society.

The theological implications of these two “dynamic equivalences”[8] are that whoever partakes in “the Eucharistic Meal of Steamed Rice/Bữa Cơm Thánh Thể” and eats this “Steamed Rice of Life/Cơm Hằng Sống” will never be hungry again and, above all, have eternal life.

My own journey from bread to rice comes to an end when I write this Preface. On the one hand, this journey is over. On the other hand, the journey continues, although it no longer focuses on the Multiplication of the Loaves in John 6, but rather on other theological discussions in the Vietnamese cultural context. In other words, I will continue to engage in dialogue with the Vietnamese culture, so the Gospel written in the Jewish context can, in the words of Pope Francis, have “a [Vietnamese] face and flesh.”[9]

[1]

Stephen B. Bevans, Models of Contextual

Theology: Revised and Expanded Edition (Manila: Logos Publications, 2003),

3.

[2]

Ibid.

[3]

Ibid., 4.

[4]

Ibid., 3.

[5]

See FABC, “Evangelization in Modern Day Asia,” in Gaudencio Rosales and C.G.

Arevalo, eds., For All the Peoples in

Asia, Vol. 1 (Quezon City: Claretian Publications, 1997), no. 12. Henceforth,

reference shall be “FAPA-1.”

[6]

Pope John Paul II, Apostolic Exhortation on Jesus Christ the Savior and His

Mission of Love and Service in Asia Ecclesia

in Asia, AAS 92 (2000), no. 20.

[7]

Pope John Paul II, Ecclesia in Asia,

no. 20.

[8]

Anscar J. Chupungco, Cultural Adaptation

of the Liturgy (Ramsey, New Jersey: Paulist Press, 1982), 83.

[9]

Nguyễn Trung Tây, “Khuôn Mặt và Thịt Da Việt Nam [The Vietnamese Face and Flesh],” Nguyệt San Đức Mẹ Hằng Cứu Giúp [Journal of Our Lady of Perpetual Help] 401 (January 2020): 44.

God is rice! Congratulations, father!

ReplyDeleteSurely God is Rice to all those who do not consume bread as staple food but steamed rice. Thanks for your insight!

Delete